In December 2005, I was invited by Oxford University to deliver the 2009 Clarendon Lectures in Management Studies and then to produce a book based on those lectures. We decided that I should try to synthesize my research, consulting, and other experiences going back to 1985 with companies ranging from Toyota, Intel, and Microsoft to Google and Apple, described in nine books and nearly one hundred articles. The result is my latest book, Staying Power: Six Enduring Principles for Managing Strategy and Innovation in an Uncertain World (Oxford University Press, 2010, and 2012 paperback). This article is a summary of the key ideas.1

Innovation and Commoditization

As I was going back over my studies of automobiles, software, computers, and consumer electronics, I realized that we had entered a new age – that of simultaneous “innovation and commoditization.” What I mean by this term is that knowledge of how to produce many different kinds of innovative products has become widespread around the world, but many of these products have already become commodities. Prices have fallen to low levels and sometimes to zero, as in the case of software. At the same time, customers are usually not content to buy the same old products. They demand new products, as well as new features and services. So companies have to deliver innovation, but in a very efficient way because it is hard to make money from products by themselves.

In computers and consumer electronics, there is a history stretching back to the 1960s and 1970s of hardware prices dropping continuously while functionality rises due to innovations in microprocessors from Intel and other companies. We are all familiar with this phenomenon in hardware but we have seen it in software as well, beginning with PC products in the 1970s and 1980s, led by companies such as Microsoft and Lotus. Then, in the 1990s, led by companies such as Netscape and then Yahoo and Google, we saw lots of Internet-based software and functionality delivered for free as what we now call “cloud computing.” And then we have the broader global phenomenon today that China can manufacture nearly any machine or consumer product very cheaply, so their prices become the world’s prices for manufactured goods. India can also deliver nearly any kind of high-technology service very cheaply as well – such as product engineering, custom software development, or back-office operations – so their prices become the world’s prices for high-tech services.

The age of innovation and commoditization has created a very difficult situation for managers in the United States, Japan, and Europe. It creates very challenging economics for managers when their products have to be priced very cheaply or at zero: it requires a different kind of thinking about business models, global logistics, and productivity. I also argue in my book that, as many tangible products have become commoditized, the value or the potential revenues and profits has shifted increasingly to more complex industry-wide platforms – global ecosystems of fundamental technologies tied to complementary products and services – as well as different kinds of value-added services. And now there really is, from the point of view of managers, very little room for error. At the same time, we have lots of ideas out there as to what are best practices for managers. It has become increasingly difficult to choose what are the most valuable principles that can truly help managers create companies that can succeed over decades and across generations of change.

There are several books – Japan as Number One by Ezra Vogel (1979), In Search of Excellence by Tom Peters and Robert Waterman (1982), Good to Great by Jim Collins (2001) – that have tried to identify best practices. However, my conclusion after reading the popular literature and a lot of the academic literature is that, on the whole, these are limited case studies with limited conclusions. Some of the studies are not very rigorous. The problems in the arguments and the data make it difficult to generalize about bigger principles. Often what seems to be a good practice in one industry, country, or time period does not transfer to other industries, countries, or time periods. We have cases where companies are very successful, and then five years later the companies are bankrupt or almost bankrupt. This actually happened to many of the firms written about in In Search of Excellence and Good to Great. The whole world is also aware that Japan has struggled for decades since the end of “the Japanese miracle” in the late 1980s.

There seem to be a variety of factors causing successful organizations to falter over time. Imitation, for example. A company may have a best practice in an area such as manufacturing at one point in time, but if most other companies follow that practice, then it is no longer a best practice and a way to differentiate the competition. The life-cycle stage, the industry structure, luck and timing have also been very important in the rise and fall of particular companies. Practices and capabilities that help new firms win in a market are very different from the skills needed to stay on top of a market once they are successful. Many of the books and articles about the best companies in a given time period tell us about the characteristics of those companies at a particular juncture but do not tell us what were the factors that enabled those companies to get to that point. Very often we see other companies that look nearly the same in terms of skills, resources, and strategies, but they do poorly. And so we need to distinguish the principles that enable a company to thrive and survive through different ups and downs and cycles of change. We need to avoid what academics call “survivor bias” in our samples when we try to generalize about success.

Another starting point for my book was to go back to my early research and try to understand what happened to Japan. There was a time in the 1950s and 1960s when Japan was not considered representative of best practice in manufacturing, engineering, or quality control. Then it overtook the West in many sectors, such as automobiles and consumer electronics. When I landed at Harvard Business School in 1984 as a postdoctoral fellow in production and operations management, I had already spent several years living in and studying Japan. In fact, the reason I learned Japanese was to more deeply understand Japanese management practices. And then what became very puzzling was how could these best practices of the 1970s and 1980s, which became known as part of the “Japanese miracle,” became seen as bad practices in the 1990s and 2000s?

Many of the practices and characteristics that we now see as weaknesses of Japan were once considered great strengths. In management, we used to praise Japan for lifetime employment, consensus management, seniority wages, company unions, and other practices that kept skills within the firm and promoted a long-term view. Now, we see these as elements of organizational rigidity and “lowest common denominator thinking” or strategy by committee. In the financial system, Japan has always managed to keep interest rates low, protect its banks, and facilitate definite financing for firms and the government. These helped capital investment and were all useful to finance growth as long as the “pie” was growing. In the 1990s, when growth stopped, these practices became weaknesses. Now, low interest rates look like an inefficient use of capital, and deficit financing looks like a lack of controls. Japan went through a period of bankrupt banks and an essentially bankrupt government.

The major conclusion is that the environment around Japan has changed. It is not so much that the best Japanese firms are no longer any good. The best Japanese firms like Toyota are still very good. But leading companies in other countries such as the United States, South Korea, China, and elsewhere have caught up and often surpassed the Japanese. Many of them learned their management practices from Japan, but Japan no longer has the same advantages in quality or productivity that it had thirty years ago. Protected sectors are still weak, and other factors such as the high yen have hurt competitiveness in exports.

At the national level, Japan is still a very rich country and actually is doing quite well. If you compare Japan to Greece, Italy, Spain, or Portugal, then Japan is doing very well. Some areas like the quality of universities or the amount of entrepreneurship can definitely be improved, but overall, Japan is not as bad off as the media has argued. In general, when you look at the histories of individual companies or countries, it is normal to go through cycles of growth and success, and then, as competitors catch up, encounter some periods of decline and stagnation. Twenty-five or thirty years ago, we read about the economic decline of America and the rise of Japan. Now we read about the rise of China, India, and Brazil. None of the markets we exist in are stagnant; they are dynamic and changing. Companies as well as nations that do well over long periods of time also need to be able to adapt.

Six Principles

This issue of what it takes for companies and nations to adapt to change brings me back to the topic of “staying power.” In my research, I have tried to step back and look deeper at companies that have done well and have managed to survive ups and downs, and come through periods of change. What kinds of ideas and practices are behind those companies? I came up with six principles, based both on my own work and that of many other researchers in the field of strategy and innovation.

1. Platforms. Not Just Products

In many markets today, companies need to think in terms of platforms, not just stand-alone isolated products. I have an iPhone in my pocket, for example. This is not just a product. Just by itself it is a piece of metal and plastic, but it is actually worth a lot to a user because of what you can do with it. It is at the center of an ecosystem of hundreds of thousands of companies that are building applications or services for it. This is an example of a platform, not just a product.

2. Services, Not Just Products (or Platforms)

The second principle is about the role of services in the lifecycle and competitive strategies of product companies. Firms in a variety of product industries have experienced commoditization and the value of their products is often shifting to complementary services or service-like versions of their products. Again, I can use the iPhone as an example. Several years ago in the United States when this first came out, one of my colleagues stood in line overnight to buy one, and he paid US$600 for it. Other people bought their phones last year and paid US$49 and actually this is the next version. It is better. However, later buyers also had to buy a two-year service contract. The design has also been copied by Samsung and many other companies-the product is becoming like a commodity, but the value (and the money) has shifted to the service contract.

3. Capabilities. Not Just Strategy

My third principle is that managers need to think in terms of capabilities, not just strategy or strategic planning. They should be building strategy on top of distinctive capabilities, whether that capability is in software technology, product design, or quality management. Strategies need to change over time, but more enduring are the unique skills and knowledge that enable a company do things that competitors cannot easily do, and to do things that customers value.

4. Pull, Don’t Just Push

The principle I call “Pull, Don’t Just Push,” is about creating real-time linkages to customers and different sources of market information, rather than just forcing out products and technologies to the market according to preset plans. The model for this idea was the original Toyota production system, which devised what we now call “Just-in-Time” inventory management. But I also talk about this principle in terms of product development such as by creating prototypes and other opportunities for feedback from customers to adjust what a team is doing. We also see pull versus push in marketing, planning, and R&D. The goal is to create systems that are flexible and responsive to new information on customers, competitor behavior, technological changes, or potential natural disasters.

5. Scope, Not Just Scale My principle about economies of scope refers to the fact that most customers today want variety; they want products and services put together in creative ways and tailored somewhat to their individual needs. Companies have to figure out how to do this efficiently, which requires utilizing knowledge, technology, and designs across different products and different kinds of customers. It is really about leveraging knowledge, not about making many copies of a particular product and trying to win over customers through better economies of scale.

6. Flexibility, Not Just Efficiency

The final principle is about flexibility, rather than too much focus on efficiency. For example, if a company builds a factory that can make ten different products rather than just one, and if the market declines for some of those other products, managers can switch easily to the products that are selling. It may cost more to create a flexible factory in terms of machinery, worker training, and supplier management, but it protects the firm against changes in the market. We can also think about this kind of flexibility in other areas such as research, product development, strategic planning systems, and service delivery. In order to thrive and survive over long periods of time, companies need to prepare for different scenarios and cultivate the ability to deal quickly with change and unexpected situations.

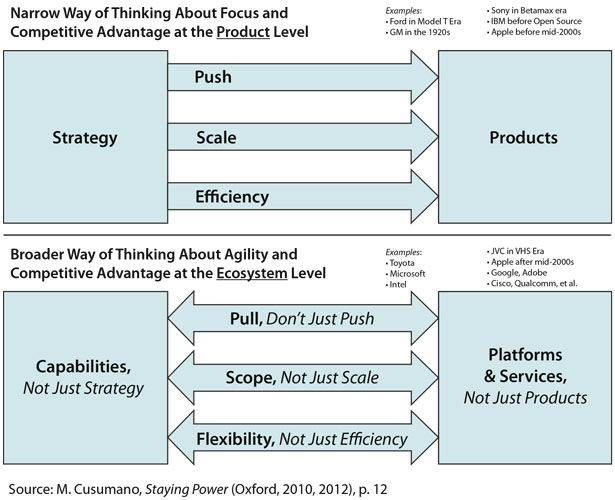

In essence, the six principles suggest that the mode of competition has changed. As outlined in the graphic below, the old competition was about products and strategy tied to products; it was about pushing out products, focusing on economies of scale, and trying to be the most efficient in your industry. But the world we live in today is much more complicated. It is a world of interrelated platforms and services, not just stand-alone products. It is a world of pull as well as push, scope as well as scale, and flexibility as well as efficiency.

Platforms, Not Just Products

Let’s look at my first principle in more depth. We can think of industry platforms as containing building blocks such as from Lego, where you can take components and build things in a very creative way, and not always what the original designer intended. Many companies use this concept of a platform internally to create families of products relying on common components. When they allow other companies to use their building blocks to create their own products or services, then we have an industry platform, not just a company-specific platform. Google search and systems technology like Android, the iPhone hardware and software, the Windows operating system and Intel microprocessors, and the Facebook application programming interfaces are all examples of well-known industry platforms. Thousands of companies have taken the components of these technologies and put them together or built on top of them in different ways. They also have built applications or services that go way beyond what the original platform companies thought about.

Usually, a platform technology by itself has relatively little value. What makes it most valuable are what we call the “complementary” products or services – applications or services that rely on that foundation technology. What is unusual about a platform compared to a product is that, the more of these kinds of complements that exist, the more valuable the platform usually becomes. The platform and the complements, and the rising number of users, generate what we call “network effects” that benefit from positive feedback loops. The more complements there are, the more users are attracted to the platform, which attract more companies to create complementary innovations, which attract more users (and advertisers), and so on.

There are really a number of different markets where we see this phenomenon of increasing value and network effects, whether it is Web search or digital media, micropayment systems, or power systems for the automobile, like gasoline versus electric batteries or hydrogen fuel cells. Once you start thinking about these technologies as platforms, the whole world becomes a series of platforms interacting with other kinds of platforms, and companies competing for dominance of different platform leadership positions. And in a platform market, the company that is likely to win or at least perform best is the company that has the best platform; it is not the company that has the best product. The example I like to use is the Macintosh versus the original DOS personal computer and then the Windows PC. Almost everyone will recognize that the Macintosh was a better product, but the PC with a relatively open Microsoft operating system was a better platform for other companies to create their own complementary products, hardware and software.

What makes for a “best product” is hard to define, but we have some ideas of what a good platform should be. A platform generally brings multiple participants or “sides” of a market together to do something in common. But to do that well, the platform has to be relatively open, so the building blocks inside of it are accessible to outside companies. The architecture of the platform has to be relatively modular so that companies can come in and extend it. The Sony Betamax VCR, the Apple Macintosh personal computer, even the first Apple iPod media player and the first Apple iPhone were largely designed as closed systems. Only the ones that were opened up to ecosystem partners – the iPhone and the iPod, along with the iTunes digital service – really became successful.

The other interesting characteristic about platform markets is they have this ability to grow exponentially related to network effects. It is possible that one company could end up with a 100 percent market share, so when we teach strategy now, we have to teach a different way of thinking. There are three conditions that lead to a case where you are likely to have a winner take all or most of the market.

First, you have to have very strong network effects between the platform and the complements. And these could be direct or indirect network effects, but the more people who adopt the platform, the more it influences other people to adopt, and that kind of effect needs to keep growing. When you have this happening, you have the potential of one winner or at least one big winner, like Microsoft in operating systems for the desktop. Google and Facebook are examples of winners who have taken most of their markets, but not all.

Second, there has to be relatively little differentiation across the competing platforms. This appears to go against conventional thinking about strategy and innovation, but really it doesn’t. In traditional strategy and innovation management, you want to encourage firms to think differently. You want to be differentiated. But for platform strategy, that is not always a good thing because it creates niches or segments that can fragment the market. To win a whole market, or most of a market, you have to copy and make sure that no one has anything different from what you have. This is one thing that Microsoft did well, for example, even though it took 20 years or so to copy the Macintosh.

Third, what we call “multi-homing” has to be difficult for complementors and users. As a company, you have to make it difficult or costly for users to adopt more than one platform as their “home” because this will also lead to a fragmented market. You have to encourage users and other ecosystem partners to choose one platform. You hope they choose your platform. This is a very simple blueprint, but we can use it to describe the strategy of companies like Microsoft, Google, or Facebook. They will all try to create strong network effects; they will all copy each other so that no one has anything that is too differentiated; and they will try to force users to use their platform and not someone else’s platform.

In conclusion, the world of platforms requires a different way of thinking about strategy and innovation. And it is not simply the old product kind of thinking that we used to have. You can have a great product with great technology, great components, and great quality control, but you are not going to win in a platform market unless you understand these more complex ecosystem dynamics and offer the best platform to users and partners. You have to understand the different ways of making money from these kinds of markets. Very often the money is not in selling the device or selling components for the device; the money is in software, content, or services of different types.

Japanese firms like Sony, historically, have been very good at making components and hardware boxes. But they have not really understood some of these more complex elements of how to compete in global platform markets, particularly with software and network technologies such as the Internet at their foundation. China and India will also have to deal with this issue of complex value chains as they lose their advantage in wage levels and costs. Companies in countries such as Greece, Italy, and Spain also do not seem well prepared for this new type of competition. Again, it is not a permanent situation because conditions will change over time. But staying power in today’s world, as described by my six principles, requires a different way of thinking, organizing, and competing.

About the Author

Michael A. Cusumano is the Sloan Management Review Distinguished Professor of Management at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Sloan School of Management, with a joint appointment in the MIT Engineering Systems Division. He specializes in strategy, product development, and entrepreneurship in the computer software business as well as Internet services, consumer electronics, and automobiles. He has been a director or advisor for several public and private companies as well as a well-known consultant and speaker. He has published 9 books, most recently Staying Power: Six Enduring Principles for Managing Strategy & Innovation in an Uncertain World (Oxford), named one of the best business books of the year by Strategy + Business magazine.

Note

1. M. A. Cusumano, Staying Power: Six Enduring Principles for Managing Strategy and Innovation in an Uncertain World (Oxford University Press, 2010, 2012 paperback). This article is based on a lecture given at the International House of Japan in January 201

2. A transcript of the full lecture is published as “Staying Power: Lessons for Japan,” IHJ Bulletin, vol. 32, no. 1, 2012, pp. 35-49.