By Dr. A. Narayanamoorthy and Dr. P. Alli

Following the announcement of comprehensive credit policy of 2004, an impression is often gained from the official statements that all agrarian problems can be set right with the enhancing of agriculture credit. The article queries whether government credit expansion policies are reaching the targeted beneficiaries and argues that enhanced credit is not enough in itself because enhanced institutional credit, without more, to agriculture in a way contributes to more of farm indebtedness.

Is the big fat institutional farm credit, of the farmers and for the farmers? As the farmers generally wait for monsoon showers and gear up to organize money to purchase farm inputs to cultivate crops, it is expected that the credit extended by banks to agriculture sector should expand during this period. If it does, who benefits from such significant increase in farm credit? This particular issue assumes paramount importance especially in the wake of the observation of The Rangarajan Committee on Financial Inclusion (2008) that a bulk of small and marginal farmers does not have access to institutional credit. Close on the heels of this Report, came the recently released Nachiket Mor Committee on Comprehensive Financial Services for Small Business and Low Income Households (2013), which observed that the agriculture sector has long distance to go before it reaches the 50 percent financial depth. Do these observations hint out at the disturbing trends surrounding agriculture credit? According to data published by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), the share of marginal and small farmers in agriculture credit disbursements by commercial banks has declined considerably, while the share of large farmers has sharply risen in the recent period. Where is the priority sector lending heading? Is it losing its track?

Following the announcement of comprehensive credit policy of 2004, an impression is often gained from the official statements that all agrarian problems can be set right with the enhancing of agriculture credit. Consequently, the focus of every budget and five-year plan deliberations has been on setting of agriculture credit targets. The Union Budget of 2013 was also no different as the country’s Finance Minister announced that the target for agricultural credit would be increased to Rs. 7 lakhs crore as compared to Rs. 5.75 lakhs crore over its previous year. Quite a few scholars have believed this quantum jump as the panacea to all evils happening in the agricultural front today. If that is so, then why incidents of farm suicides have risen from 1,08,593 in 2000 to 1,34,599 in 2010? If such massive credit expansion policies of the government are not reaching the targeted beneficiaries, then where is it going?

Where Is Inclusiveness Quotient?

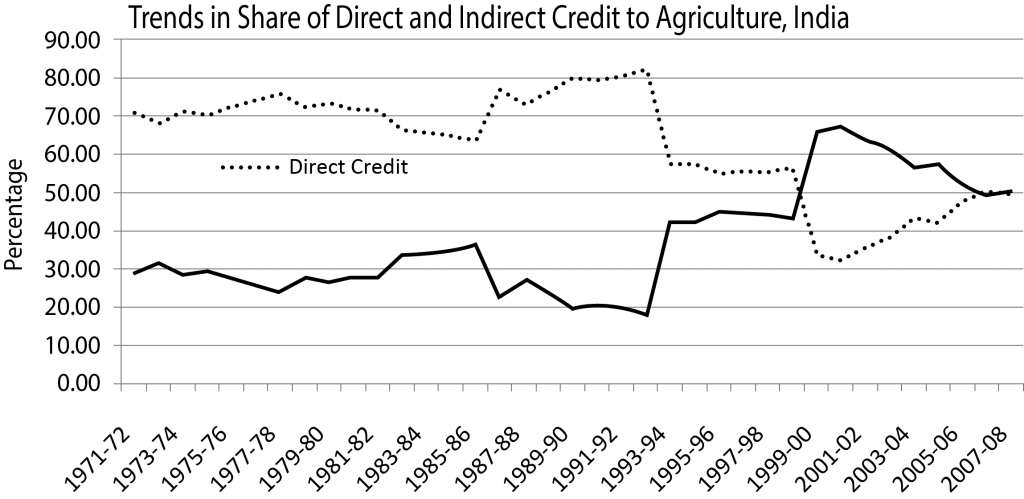

A defining feature of agriculture credit in the recent past has been the doubling of institutional agriculture credit (DAC) over a three-year period beginning from 2003-04. Since then the annual credit flow to agriculture has invariably been surpassed every year from Rs. 2,48,604 crore in 2004-05 to Rs. 5,11,029 crore in 2011-12. However, a closer look at the data on agriculture credit reveals that what is termed as agriculture credit may have very little to do with agriculture. During 1990-91, of the total credit issued to agriculture about 20 percent was accounted for by indirect finance in form of loans to companies that make farm inputs, state electricity boards, agribusiness companies, etc. This has increased to over 50 percent during 2007-08 for which we have data on indirect and direct flow of credit from RBI. When we divided this period into pre-DAC (2000-01 to 2003-04) and period of DAC (2004-05 to 2007-08) astonishing results were revealed. During pre-DAC, the direct and indirect credit grew at a CGR of about 13 and seven percent respectively, whereas during the period of DAC, it was about 12 and 14 percent respectively. The implication is that between pre-DAC and period of DAC, the growth rate of direct credit has gradually slowed down, whereas that of indirect credit has recorded a big jump. Since complete data on agriculture credit is not available from 2007-08 onwards in any of the data sources, we could not make an analysis as to what has happened to the trend in direct and indirect credit during the post-DAC.

However, going by the trends during the DAC, it can very well be presumed that the tilt would have been increasingly towards the indirect credit. Is this what the state means by priority sector lending? An increase in indirect finance is necessary to improve the productivity capacity of farmers, but is it at the cost of undermining of direct finance? When there is a serious physical limitation to the delivery of agriculture credit, how can we expect the farmers’ outcry to recede?

Boon or Bane?

Given the fact that credit facilitates the needed liquidity to farmers, enhanced farm credit will not always produce desired results. When loan money is extended to farmers with the hope of assisting them in their farm needs, they can repay the borrowed loan only when they are able to get a remunerative price for their produce. In the absence of such a price if more of fresh loans are extended then the borrowed loan gets piled up making them indebted to institutional credit as well. This is how agriculture credit is a boon as well as a bane to farmers.

The policy makers need to understand the ground reality that the well being of the farmers cannot come by opening the credit tap alone. Enhanced farm credit is very much needed to boost the farm productivity, but if coupled with affordable farm inputs and a viable MSP, will indeed provide the desired results. A prudent mix of required farm inputs especially through investing and popularizing heavily on the method of drip irrigation, System Rice Intensification (SRI) and restructuring the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS) can drastically bring down the cost of cultivation. Such initiatives can provide increased farm productivity; an assured income that can take care of their family needs and leave them with a little surplus to sow the next crop. Instead, if the state continues to focus on enhancing the farm institutional credit without addressing all these issues then the infamous quote of Sir Malcolm Darling that “the Indian farmer is born in debt, lives in debt and dies in debt” will continue to haunt the farm sector.

About the Authors

Dr. A. Narayanamoorthy is working as Professor and Head, Department of Economics and Rural Development, Alagappa University, Tamil Nadu, India. He specializes in irrigation economics and policy issues of Indian agriculture and has widely published in international and national journals. He is a recipient of the prestigious Professor Ramesh Chandra Agrawal Award of excellence awarded for the outstanding contribution in the field of agricultural economics by the Indian Society of Agricultural Economics, Mumbai. The National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD) has also awarded the coveted NABARD Chair Professor position to him. He served as a member of the policy committees constituted by the Government of India, New Delhi.

Dr. P. Alli is currently working as Assistant Professor in Economics Division, Vellore Institute of Technology University, Tamil Nadu, India. In collaboration with Dr. A. Narayanamoorthy, she has produced credible research papers in prestigious journals viz., Indian Journal of Agriculture Economics, besides being a regular contributor to some premier national dailies, such as The Business Line, The Financial Express and Deccan Chronicle.